“当时用了101名中国人做实验,对吗?”

繁体“当时用了101名中国人做实验,对吗?”

“没有,没有那么多……”

“One hundred and one Chinese were used during the experiments, correct?"

"No, no, not that many ..."

这是1981年,日本北里大学医院的知名微生物学家笠原四郎(Shiro Kasahara)与记者对话中的一幕。翻译是日本记者西里扶甬子(Fuyuko Nishisato),她当时正为英国独立电视台的一位记者担任口译。

That was part of a conversation that took place in 1981 between Shiro Kasahara, a respected microbiologist from the Kitasato University Hospital and Research Unit in Japan, and Fuyuko Nishisato, a Japanese journalist acting as a translator for a reporter from Independent Television News in the United Kingdom.

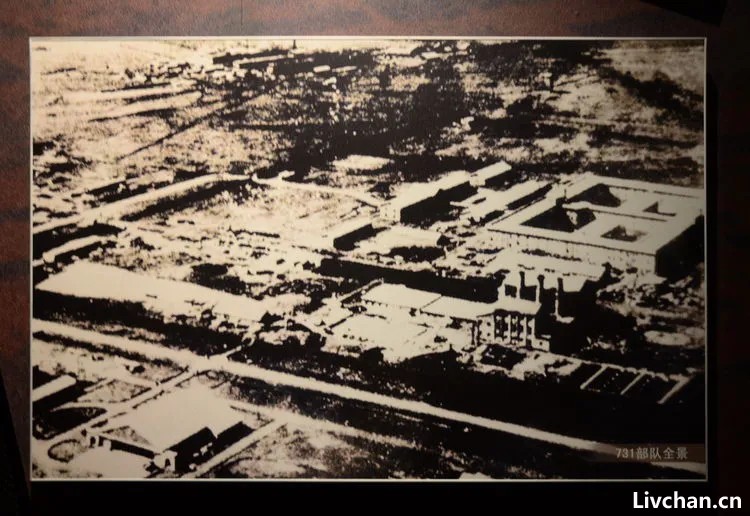

所谓“实验”,其实是活体解剖等残酷的人体试验。七十多年前,笠原还是“731部队”的一员。该部队是日本关东军秘密的生物战研究与开发机构,驻扎在中国东北哈尔滨平房区,该地区1932—1945年间属伪满洲国。

The "experiments" involved human vivisection and were conducted more than seven decades ago when Kasahara was a member of Unit 731, the Japanese Imperial Army's covert biological warfare research and development division. The unit was based at Pingfang on the outskirts of Harbin, Heilongjiang province, in Northeast China, which was part of a Japanese puppet state known as Manchukuo, in the area of Manchuria, between 1932 and 1945.

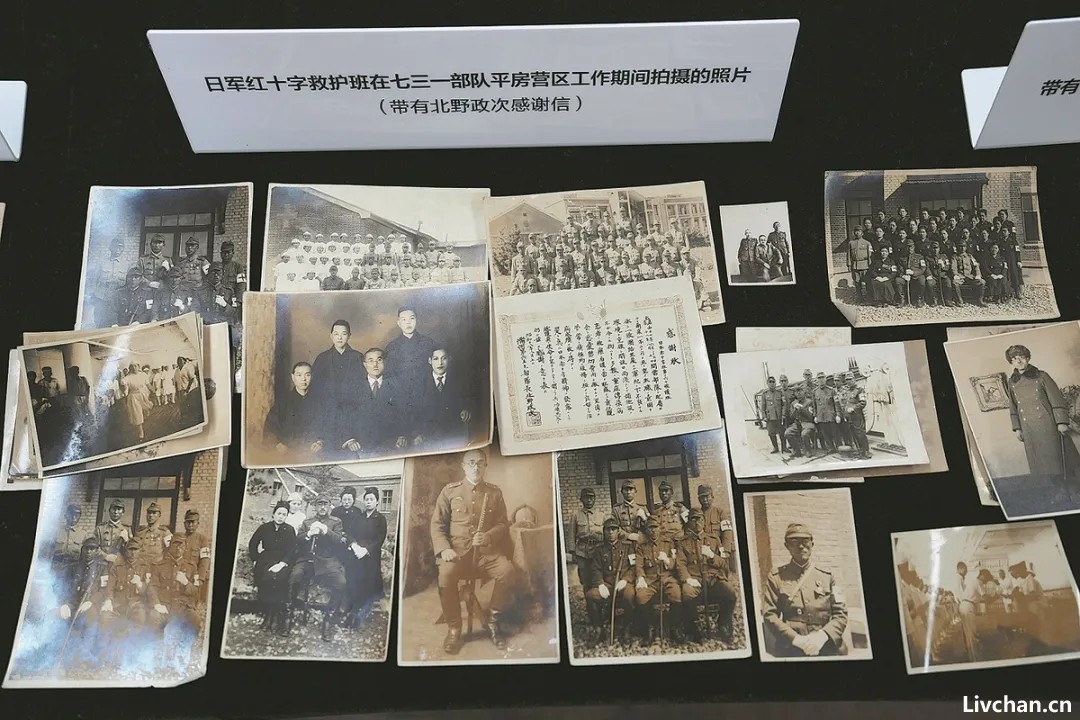

731部队在哈尔滨平房的旧址

“101”这个数字源于笠原及其同僚在20世纪40年代发表的几篇关于流行性出血热的医学论文中出现的“实验对象”总数。当时,这种由蜱虫传播的疾病在日军中肆虐。为了寻找治疗方法,他们竟以活人作为试验品。

The number 101 was mentioned because it was the total number of subjects that appeared in several medical papers about epidemic hemorrhagic fever written by Kasahara and his colleagues in the 1940s. The disease, which is transmitted by ticks, was rampant among Japanese soldiers at the time, so they decided to use human guinea pigs in their attempts to find a remedy.

西里扶甬子回忆:“上世纪30年代末到40年代初,大约有3000人——大多是反抗日军的中国男子——被宪兵队抓捕送往平房的731部队,在那里充当活体实验品。很多人惨遭解剖。笠原对任何关于‘伪满’的问题都不愿意谈,但在人体实验这个事情上却极力为自己辩护。”

"In the late 1930s and early '40s, an estimated 3,000 people, mostly men who had resisted the Japanese, were captured by the Kempeitai, the Japanese army's version of the Gestapo. They were sent to Unit 731's sprawling compound in Pingfang, where they became human guinea pigs in the research and development of biological weapons. Many were subjected to vivisection," Nishisato said. "Reluctant to enter into any discussion about Manchuria, Kasahara was very defensive about the human experiments."

“信不信由你,战争年代,许多日本医学界人士都认为能去平房用活人做实验是一种特殊待遇。” 西里说,“在平房,他们每天会填表申请,注明第二天需要多少实验对象。这些人被称为‘丸太’——在日语中意为‘木头’。”

"Believe it or not, during wartime, many Japanese medical professionals felt privileged to be able to go to Pingfang and use human beings in the laboratory," Nishisato said. "They would fill in forms stating how many subjects they wanted to use the next day. The human guineas pigs were referred to as maruta, or "logs", in Japanese.

在侵华日军第七三一部队罪证陈列馆展出的部分图片 图源:新华社

“这些‘研究者’们写出了二三十篇医学论文,在这些论文中他们把实验对象称作‘满洲猿’。战后,不少人甚至凭借在平房得到的‘成果’获得博士学位。”她补充道,“我还采访过几位当时在731部队设施附近做杂工的中国人。他们说能感觉到那里正在发生某种不可言说的事情,却完全不清楚细节。当然他们不会知道——那超出了人类的想象!但战争年代,整个日本医学界都知道在那里(哈尔滨平房)发生着什么,区别只是多少而已。”

"Between them, they produced a couple of dozen medical papers, in which the human guinea pigs were referred to as 'Manchurian apes'. Postwar, many received doctorates based on their 'findings' in Pingfang," she added. "I interviewed a few Chinese who did unskilled work in the vicinity of Unit 731's facilities. They said they sensed that something unspeakable must be going on, but they didn't know exactly what it was. Of course they didn't know-it was beyond their wildest imaginings! However, the entire Japanese medical world, more or less, knew during the war."

1981年,日本作家森村诚一出版了小说《恶魔的饱食》,揭露了731部队的罪行,震惊了全世界。各国记者纷纷赴日采访。西里当时受雇于英国独立电视台,负责调查与协调工作。从那时起,西里便投入了长达四十余年的时间对这段历史进行研究,参与制作了BBC、NBC、美国历史频道等多家媒体的纪录片。

In 1981, Japanese author Seiichi Morimura published his book The Devil's Gluttony, a historical novel that exposed the crimes committed by Unit 731. The world was shocked and reacted by sending reporters to Japan. Nishisato was hired by the Independent Television News to do research and coordination for their documentary film unit," she recalled. And that was the beginning of over four decades of research into Japan's wartime crimes.

这些研究把她带到平房,以及哈尔滨其他仍有受害者家属生活的地方。

“直到20世纪90年代,黑龙江、吉林省档案馆公布了日军宪兵队‘特别移送’的文件,很多家庭才第一次知道了亲人们下落。当年溃逃的日军没能完全销毁这些档案。”西里说。她还提到一位朱玉芬女士,其父亲和叔父被宪兵队抓走后失踪。档案里找到了叔父的照片,而她父亲的影像却再也没能留下。于是朱女士一直随身携带叔父的照片,因为知情者都说她父亲和叔叔的人容貌极其相似。

That research led her to Pingfang, where many people perished, and other parts of Harbin, Heilongjiang province, where victims' families still live.

"Many families had no idea about the whereabouts of their loved ones until the 1990s, when crucial Kempeitai 'special transfer' files were disclosed by the provincial archives in Heilongjiang and Jilin-files that the defeated Japanese army had no time to destroy completely back in 1945," said Nishisato.

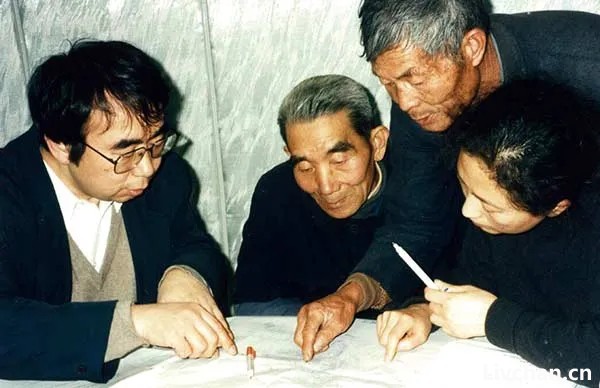

四十余年关注、研究日军七三一部队在华罪行的日本记者西里扶甬子

法庭上的努力

“怀疑与不信任”——这是日本律师一濑敬一郎(Keiichiro Ichinose)在1995年首次访问浙江崇山村时,从村民眼中读到的情绪。

For Keiichiro Ichinose, a Japanese lawyer, "doubt and distrust" were the emotions he read in the eyes of the people who surrounded him during his first visit to Chongshan, a village in Zhejiang province, in 1997.

上世纪40年代初,日军在江西、浙江多地发动大规模细菌战。崇山村因鼠疫死掉了约400人,是当时这个村庄人口的三分之一。

“感染者们的惨状惊人:他们通常骤然发高烧,挣扎数小时或数日后痛苦死去,尸体往往被草草掩埋。几乎每一扇紧闭的门后,都有一个无助的灵魂在挣扎。”一濑说。

"In the early 1940s, the Japanese launched large-scale germ warfare in many parts of the provinces of Jiangxi and Zhejiang. Chongshan lost one-third of its population-about 400 people-to bubonic plague after the bacteria was spread by the Japanese," he said. "The stories are painfully similar: people suddenly developed a high fever, struggled for hours or days, died miserably and then were buried, often hastily and secretly. Behind every tightly closed door was a suffering, helpless soul. The whole picture was hellish."

在王选(右)担任翻译的帮助下,一濑敬一郎(左)在浙江省收集细菌战受害者的证词

从1995年至今,一濑已近百次来华,收集证据与证言,帮助受害者起诉日本政府,要求就细菌战与无差别轰炸索赔。祖籍崇山村的中国社会活动家和日军细菌战历史研究者王选女士数十年来也参与其中,陪伴他走进法庭与村庄,并为其担任口译。

Ichinose has visited China nearly 100 times since 1995, to gather evidence and collect testimonies for court cases in which victims and their families sued the Japanese government for compensation for the use of germ warfare and indiscriminate bombing during the invasion of China.

Wang Xuan, a Chinese researcher and activist whose involvement in the lawsuits spans several decades, has stood beside Ichinose in court and in Chongshan. As a fluent speaker of Japanese she has translated for him during his meetings with victims.

“我必须说,起初一濑就像许多前来中国会见细菌战受害者的日本律师一样,完全没有意识到他的出现本身会给村民们带来怎样的心理冲击。”王选说,“他们(日本人)并不总能敏感地意识到自己是‘侵略者的后代’。”

"I have to say that at the beginning, Ichinose, like many of the Japanese lawyers who came to China to meet plaintiffs, was completely unaware of the mental impact his very presence had on the villagers. They (the Japanese) were just not always sensitive to the fact that they were 'the descendants of the invaders'," Wang said, making quote marks in the air.

日本律师一濑敬一郎(中)2015年在浙江衢州细菌战受害者纪念馆拍摄因日本生物武器而遇难者名单 韩强摄

作为原告团团长,王选在1997至2007年间主导了一起赔偿诉讼案,该案一路上诉,从东京地方法院最终打到日本最高法院。最鼎盛时期,原告团律师多达224名,全都是日本人,其中一濑是核心成员之一。整个团队由土屋公献担任团长,一濑为事务局局长。

As head of the plaintiffs' group between 1997 and 2007, Wang was at the center of a compensation case that went all the way from a Tokyo district court to Japan's Supreme Court. At its largest, the lawyers' group for the plaintiffs numbered 224, all of them Japanese, with Ichinose as a core member. The group was led by Khoken Tsuchiya, a one-time chairman of the Japanese Bar Association.

2003年9月,王选(右起第六位)与日本律师及和平人士在东京日比谷公园举行示威,要求日本政府就其在华发动细菌战道歉并赔偿

良知与忏悔

“据我所知,土屋是第一个对受害者说‘不用感谢我们’的日本人。”王选回忆道,“他的谦卑是发自骨子里的。”

"As far as I know, Tsuchiya was the first Japanese to say 'No need to thank us' to the victims," Wang recalled. "His humility was deeply rooted."

年轻时的土屋公献

1943年12月,日本战败在即,20岁的土屋从高中退学,加入日本海军。在中国东北旅顺受训后,他被派往父岛(东京本土以南1200公里处),在那里忍受饥饿和美军持续不断的轰炸,直到1945年8月15日,日本宣布无条件投降。

In December 1943, with defeat for Japan looming, 20-year-old Tsuchiya left high school and joined the Japanese Imperial Navy. After receiving training in Lyushun, a port in Northeast China, he was dispatched to Chichijima, or "Father", Island, 1,200 meters south of mainland Tokyo, where he endured hunger and constant US bombing until Aug 15, 1945, when Japan formally announced its surrender.

在土屋去世前一年的2008年,他的日文自传《律师之魂》出版了。书中土屋描述了一位战友的死亡:“一颗子弹从他口中射入,打穿了头颅和头盔。他的眼球迸出,鲜血从口中喷涌而出……一股寒意从我心底升起。”

In his autobiography The Spirit of Lawyers, published in Japanese in 2008, the year before he died, Tsuchiya described the death of a fellow soldier. "A bullet shot through his mouth, punching holes in his head and helmet. His eyeballs popped out as blood spurted from his mouth ... a chill rose from the bottom of my heart," he wrote.

另一个令他难以忘怀的场景是,一名学习剑道的日军同僚处决了一名美军战俘——年仅22岁的少尉沃伦·厄尔·沃恩 (Warren Earl Vaughn)。在行刑前几天,土屋还曾抽空与这位比自己年长一岁的年轻美国海军陆战队队员交谈。而在沃恩被杀的那个夜晚,他出面阻止了两名饥饿的日军士兵掘墓食尸。

美军少尉沃伦·厄尔·沃恩

“我告诉他们,他是英勇赴死的,必须让他安息。第二天,我将此事上报给上级,但得到的反应却是:‘你为什么要阻止他们?’”土屋在书中回忆道。

Another incident that stayed with him was the execution of a US prisoner of war, 22-year-old second Lieutenant Warren Earl Vaughn, by a fellow soldier and kendo practitioner. Days before the execution, Tsuchiya found time to talk with the young US marine, who was only a year older than himself, and on the night of Vaughn's death, he intervened when two ravenous soldiers attempted to dig up the body and eat it. "I told them that he had died bravely, so they must let him rest in peace. The next day, I reported the incident to my superior, whose reaction was: 'Why stop them?'" Tsuchiya recalled in his book.

“我成长于一个良知被践踏的时代。我的青春被浪费,而更多人的青春则被直接斩断。” 土屋写道,“回首往事,我意识到,在邪恶面前保持沉默,本身就是一种罪恶。”

从1997年到他2009年以86岁高龄辞世,深受同僚尊敬的土屋一直致力于在法庭内外揭露日本的战争罪行。采访幸存者让他的足迹从日本延伸到中国,而向公众讲述战争的残酷与邪恶,又让他走向美国与加拿大。

"I grew up in an era when conscience was trampled. My own youth was wasted, while many more were cut short," he wrote. "Looking back, I realize that silence in the face of evil is a sin."

Between 1997 and his death at age 86, Tsuchiya, who was highly regarded by his peers, devoted himself to exposing Japan's wartime crimes, in and outside courts of law. His mission took him from Japan to China, where he interviewed witnesses, and to the US and Canada, where he spoke to audiences about the evils of war.

王选常常和他同行。“他会主动帮我提沉重的行李箱——这在日本男人中这并不常见。他始终是个沉稳、父亲般的存在。”她说,“在中国,他能轻松融入当地百姓的生活,常常在他们家中吃饭喝酒。然而在法庭上,他却是如此强有力:简洁、锋锐、令人无可辩驳。”

Wang frequently accompanied him. "He would offer to carry my heavy suitcases, something unusual among Japanese men. He was always a steady, fatherly figure," she said. "While in China, he blended easily with the locals, eating and drinking at their homes. Yet he was always such a force in court; concise, powerful and irrefutable."

作为律师的土屋公献

西里指出,土屋并非唯一一位后来深深憎恨自己曾经热衷的那场战争的日本旧军人。

According to Nishisato, Tsuchiya was not the only former Japanese combatant who came to hate the war they had once avidly fought for their country.

“1981年,我采访了秋元寿惠夫(Sueo Akimoto)——一名曾在平房的731部队工作的血清学家。”她说,“731部队的创始人和部队长石井四郎当初用‘可以来中国做研究’的理由说服了他。秋本后来才发现真相,却已无法从这座‘死亡工厂’脱身。战后,他因羞愧而拒绝重返医学界,转去教授X光扫描技术,直到退休。”

"In 1981, I interviewed Sueo Akimoto, a serologist who had worked at Unit 731 in Pingfang. He told me that Shiro Ishii-the unit's commander and head of the Laboratory of Epidemic Prevention at the Army Medical College in Tokyo-convinced him that he could do 'research' in China," she said. "Akimoto later discovered the truth, but was unable to leave 'the Factory of Death'. When he returned to Japan at the end of the war, he was so ashamed that he chose not to go back into medical service, but to teach X-ray scanning techniques until his retirement."

但并非所有人都感到愧疚,或愿意承认这种愧疚。文章开头提到的战争期间曾进行人体实验的微生物学家笠原,战后在让日本学界名声显赫,却始终毫无悔意。

Not everyone felt guilty, or would admit to feeling so. Kasahara, the microbiologist who performed experiments on humans and became a respected figure in his field after the war, remained unrepentant.

固执的否认

一濑深知这种否认心理有多么顽固。他已故父亲的右臂和右髋都带着战争的伤疤。“小时候,我被那些疤痕深深吸引。长大后,我问过父亲:你曾经杀过中国人吗?” 一濑回忆道,“然而父亲终其一生都没有回答这个问题。他在参军前曾师从一位著名教授学习中世纪艺术史。”

Ichinose is aware of how persistent that sense of denial can be. His late father's right forearm and right hip carried scars from the war. "When I was little, I was mesmerized by them. Later, as I grew up, I asked my father: did you ever kill any Chinese?" he said. "Throughout his life, my father, who had studied medieval art history under a leading professor before he joined the army, never answered that question."

一濑与王选、土屋一起于1997年至2007年期间在日本法院为中国细菌战受害者打官司。那场官司最终赔偿请求被驳回,但法院却确认了所有事实——从细菌战到人体实验。

“这本身就是一种胜利。”一濑说。

Between 1997 and 2007, Ichinose fought along with Wang and Tsuchiya in courts in Japan . The demand for compensation was rejected, but the court accepted all the facts, from germ warfare to experiments conducted on humans.

"That was a triumph," Ichinose said.

日军占领期间的731部队驻所航拍图

在自传中,土屋承认自己曾离战争罪行只有一步之遥:“原本处决那名美军少尉的任务是交给我的。我痛恨这件事,却没有拒绝的理由。然而在行刑前一天,我的上级带着些许歉意通知我,说已有别人自荐执行此任务。”

In his autobiography, Tsuchiya admitted that he was just one step away from committing a war crime: "The job of beheading the US lieutenant was originally handed to me. Although I hated it, I was in no position to refuse. However, the day before the scheduled execution, I was informed by my superior, who was slightly apologetic, that another person had recommended himself."

战后,那名执行斩首的日军士兵请求知道实情的其他士兵不要将他交给美军审讯。最初他也的确逃过了追查,回到家乡,又考入东京的一所大学。但1946年春天,消息传来,美方已经查明真相并在寻找他。他当晚便从东京回到家乡,不久后便自尽身亡。

When the war ended, the executioner begged his peers not to give him away to US interrogators. Initially, he escaped detection and returned to his hometown, later enrolling at a university in Tokyo. However, in the spring of 1946, news came that the US authorities had discovered the truth and were looking for him. He returned home from Tokyo that night and soon killed himself, according to Tsuchiya's book.

“我曾被欺骗,以为自己是在打一场‘荣誉之战’,却最终明白,侵略者身上没有任何荣誉,只有耻辱与痛苦。我本可能死于一种不光彩且毫无价值的死亡;但如今,我要用余生为正义而活。”土屋在书中写道。

"I was cheated into believing that I was fighting a war of honor, only to realize that there was no honor in being an aggressor-only shame and pain. I could have died a disgraceful and unworthy death; now, I will live for justice until I die," the lawyer wrote.

记者:赵旭

来源:中国日报双语新闻

特别提示:如阁下阅有所得,亦是缘分。若您不吝分享转发,便是为正能量添薪续火,既助力本站发展壮大,照亮他人路途,亦点亮自身福田,涵养自身的浩然之气!感谢雅鉴。